When those sworn to protect are the predators, who will protect our daughters in Sierra Leone? The answer must be: We will. All of us. Together as Sierra Leoneans.

by Fatima Babih, EdD

The Scandal That Won’t Die

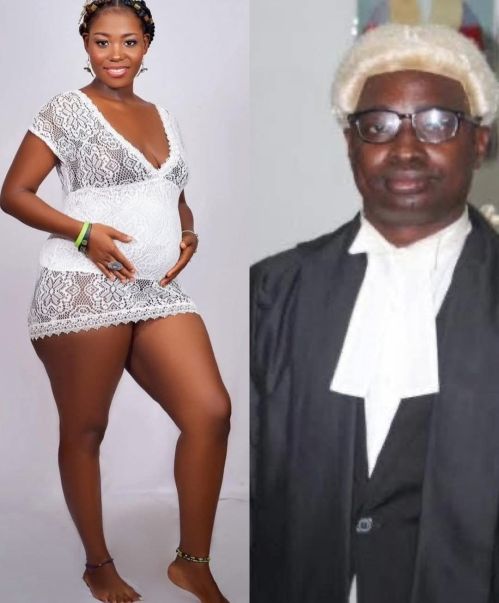

Sierra Leone’s social media has erupted over a scandal that exposes the rot at the heart of our justice system. At its center stands Appeals Court Judge Justice Momoh Jah Stevens, who filed a domestic violence case against his alleged mistress, 21-year-old Fourah Bay College law student Edwina Hawa Jamiru, mother of his child.

This is not merely a courtroom drama. It is a national reckoning about power, predation, accountability, and the character of men who preside over our justice system.

A Necessary Clarification

Before proceeding, let me be unequivocally clear: I condemn violence against anyone by anyone, regardless of gender, age, or circumstance.

If Ms. Jamiru engaged in violent behavior toward Justice Stevens or anyone else, that conduct deserves appropriate legal consequences. Violence is never acceptable, and victims of violence deserve protection under the law, even when the victim holds power and the alleged perpetrator does not.

However, condemnation of violence cannot be used as a shield to avoid accountability for exploitation, abuse of power, and the broader systemic failures this case exposes. We can, and must, condemn violence while simultaneously examining the power dynamics, institutional complicity, and patterns of predation that brought us to this moment.

This is not about choosing sides between a judge and his mistress. This is about demanding accountability from those who hold power and asking hard questions about the institutions that enable exploitation while claiming to deliver justice.

A Timeline of Trauma

The public record on social media tells a damning story about Edwina Hawa Jamiru:

First, Ms. Jamiru released a video, incoherent with distress, accusing Justice Stevens of child abandonment and dereliction of parental responsibility. Her plea was simple: financial support for their child, money she was no longer receiving.

Then, a second video emerged. This time, Ms. Jamiru appeared at a police station, visibly shaken, pleading not to be jailed, apologizing profusely, and promising to stay away from the judge. What happened between these two videos? What pressure was applied? Who intervened?

Next, an audio clip surfaced, allegedly Ms. Jamiru’s voice, begging Justice Stevens not to abandon their relationship because she loves him. She promised to keep their affair hidden from his wife, to respect his family, and pleaded for continued support for their child.

But the most chilling revelation is from an older video interview of Ms. Jamiru before this case: In that video, she is recounting how, in her final year of secondary school, she was raped by an unnamed soldier in the Sierra Leone army. In that interview, she did not wallow in victimhood. Instead, we see an eloquent young woman emphasizing her resilience, her determination to transcend trauma, and her journey to Fourah Bay College to study law, perhaps seeking justice in the system that had failed her as a teenager.

Compare that hopeful, articulate young woman to the desperate, broken voice in recent recordings makes Justice Stevens’ case against her not just a scandal. This is a young woman who has faced a pattern of trauma inflicted by men in uniform, military and judicial, who wield power over young, vulnerable girls in Sierra Leone.

Justice Stevens’ Legal Trap

The truth is that Edwina Hawa Jamiru is a traumatized young woman, a serial victim of powerful men. First raped as a teenager by a soldier and now exploited as a “side chick” by a married senior judge old enough to be her father.

Justice Stevens’ decision to file a domestic violence case against Ms. Jamiru is not just another victimization; it is a spectacular act of legal self-incrimination.

By invoking the Domestic Violence Act of 2007 against Ms. Jamiru, Justice Stevens may have cornered himself. The Act defines a domestic relationship as one where parties are:

(a) married (past or present),

(b) in an intimate relationship (past or present),

(c) members of the same family, or

(d) living or having lived in the same household.

On narrow technical grounds, Justice Stevens qualifies under subsection (b) to file his case. But here’s what he has also admitted by invoking this law:

- That he had an “intimate relationship” with a young college student

- He impregnated her when she was only 19 years old

- He engaged in an extramarital affair

With all these admissions, Justice Stevens may have exposed himself and Sierra Leone’s judiciary as an institution allegdly run by predators.

The Question No One Is Asking

But the most troubling question is not being asked in all the commentaries: When exactly did Stevens’ “intimate relationship” begin with Ms. Jamiru? Did it start before she turned 18? If so, this case transcends infidelity and scandal; it becomes a criminal child sexual exploitation case.

And even if the relationship began after her 18th birthday, a senior judge’s “intimate relationship” with a teenager he impregnated at 19 is exploitation masquerading as romance.

Therefore, in attempting to expose Ms. Jamiru as a threat to his household peace, Justice Stevens may have exposed himself as a predator hiding behind a black robe, weaponizing the very law designed to protect vulnerable women and girls like Edwina Hawa Jamiru.

This Scandal Exposes The Judiciary

As an advocate for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, someone who has spent years watching helplessly as the Sierra Leone judiciary mishandles such cases, I find this scandal enraging but utterly unsurprising.

For years, we have documented how judges systematically destroy rape cases involving adolescent girls:

- Endless adjournments that exhaust victims

- Technical dismissals that ignore justice

- Sentences so lenient they mock the crime

- A culture of silence that protects perpetrators

And now, Justice Stevens’ case forces us to ask the question we’ve whispered for too long:

Are Sierra Leone judges destroying cases involving adolescent girls because too many of them are themselves preying on young girls?

How else do we explain a judiciary so comfortable in disregarding the daily exploitation of girls in that country?

A Judiciary That Protects Itself, Not Women

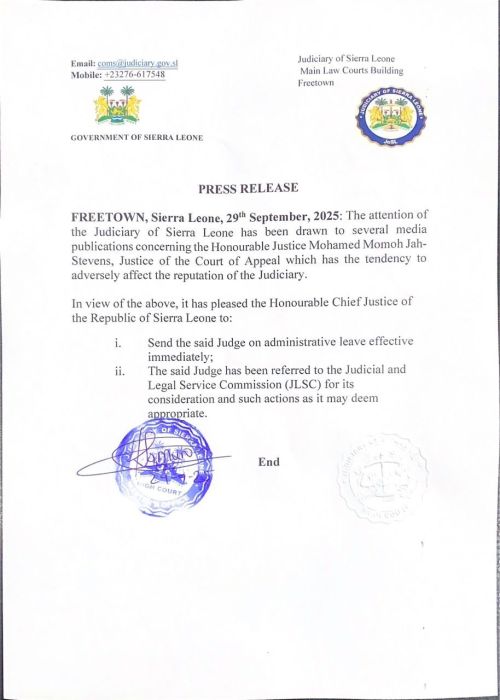

After days of social media firestorm, the Judiciary of Sierra Leone finally responded with an official Press Release, that Justice Stevens was placed on “administrative leave” (most likely with full pay).

But reading the stated reason carefully, it says: “to protect the reputation of the judiciary.”

- Not to ensure accountability.

- Not to protect a vulnerable young woman.

- Not to investigate potential criminal conduct.

- Not to send a message that the judiciary will not tolerate the exploitation of girls.

The only thing being protected is the institution’s public image.

The press release does not condemn Justice Stevens’ alleged involvement with a very young college girl. It does not address the power imbalance, the age gap, or the pattern of exploitation. It offers no concern for Ms. Jamiru’s well-being or the welfare of their child.

Justice Stevens is sent on paid vacation, not to face consequences, but to wait out the scandal in comfort while the institution circles its wagons.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Suppose Sierra Leone’s judiciary is serious about reform, about honestly administering justice. In that case, it must stop hiding behind carefully worded press releases and confront an ugly truth: Girls and women are not safe in Sierra Leone, not even from the very men who swear oaths to uphold justice.

This is not just Edwina Hawa Jamiru’s story. She is the current face of countless young women across Sierra Leone, in junior and senior secondary schools, on college campuses, in workplaces, and in courtrooms seeking justice. Young women who are silenced, shamed, blamed, and sacrificed. At the same time, powerful men walk free, protected by institutions that value reputation over righteousness.