By Dr. Fatima Babih

Our heartfelt condolences to the families, friends, and communities of Sia Fatmata Kamara and Mariama Bah. May the Almighty grant them mercy and eternal peace for their souls in Heaven. These two beautiful, promising young African women lost their lives on two continents to Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) just days apart. These tragic events shed light on a normalized phenomenon in most West African societies that demands urgent attention and action.

In mid-August 2024, Freetown, Sierra Leone, witnessed the brutal death of 28-year-old Sia. Her longtime boyfriend, Abdul Kpaka, stands charged with her murder. Kpaka brought Sia’s lifeless body to a hospital, claiming she had suffered cardiac arrest. However, an autopsy revealed several broken ribs and injury to her spinal cord, indicating a savage beating as the cause of death.

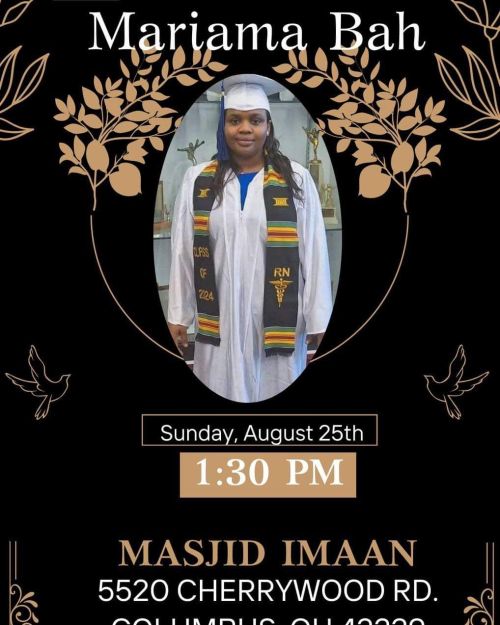

As Sierra Leone grappled with Sia’s brutal and untimely demise, another tragedy struck. On August 22, 2024, in Columbus, Ohio, 32-year-old Mariama Bah fell victim to IPV. Her 55-year-old Guinean husband, Hassana Jalloh, has been charged with her murder after allegedly bludgeoning her to death with a hammer and a knife.

Domestic Violence (DV) is violence perpetrated by a family member, household member, or community member against another. Intimate Partner Violence, a subset of DV, specifically involves violence between intimate partners in marital or romantic relationships.

Even though these deaths have shocked many, the underlying issue of IPV against women, which the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) conservatively puts at 62% in Sierra Leone, is sadly typical in West African societies.

IPV is insidious, and that is because it is most often treated with silence by the victim and those around her. The overwhelming majority of IPV incidents in West Africa involve men as the perpetrators and women as the victims. This stark imbalance isn’t a coincidence but rather the result of deeply ingrained societal norms and expectations passed down through generations.

A Sierra Leonean woman, as an example, knows that if she were to raise her hand against her partner (husband or boyfriend), even in self-defense, she would face far more than just legal consequences. The community would label her a pariah, a woman whose children are cursed by her disrespect of her husband or the father of her children.

This stigma against female perpetrators of IPV, even in self-defense, acts as a powerful deterrent for IPV against men in West Africa. It ensures that women think twice before even considering defending themselves during an attack by their intimate partner. Most West African women who report IPV they endure to authorities in Western countries where they reside are often met with their community’s condemnation, frequently accused of using police to ruin the life of a man working hard to support his family back home.

Regardless of where they live, it is common for an older West African woman to say to her younger niece, who confides in her, that she wants to leave her psychologically and physically violent husband,

“You mean to tell me that you want to leave such a good breadwinner in our family because of that small beating he gave you? If I show you the scars your uncle has left on my body in the past 20 years, you will count yourself lucky.”

Most West African women grow up with this social conditioning that a woman who bears her husband’s wrath with silent endurance will be blessed with prosperity. Older women often tell stories of women who endured physical, verbal, and psychological abuse from their husbands, only to be rewarded later in life with successful children and comfortable living, even if one of those children is a notorious thief or corrupt politician.

These cultural beliefs, deeply rooted in West African societies, paint suffering as a virtue and silence as strength for a woman. Therefore, most women never report IPV to family, friends, or the authorities until it’s too late.

Meanwhile, there are no cultural taboos for IPV by male perpetrators against women. In fact, it is normalized in West African societies such as Sierra Leone, where a man beating his wife is often excused, and the assault is minimized. This normalization of male IPV has led to a culture of disregarding men’s transgressions in the Sierra Leonean homes.

Due to these societal attitudes that excuse or minimize their actions, men are primarily protected from the consequences of IPV, even by law enforcement. For instance, in Sierra Leone, most often, a Magistrate Judge would tell the female victim of IPV to take her case to her family or tribal head. Consequently, Sierra Leonean women, regardless of their socioeconomic standing, even those living in Western countries, are conditioned to expect and accept IPV in their relationships.

This acceptance has led to underreporting of incidences, women’s reluctance to defend themselves during physical assaults, and perpetuation of the cycle of violence, as most abused women would blame and assault “the other woman.” for their partner’s maltreatment.

We can all rest assured that the day Abdul Kpaka beat Sia to death was not the first time he assaulted her. The day Hassana Jalloh hammered Mariama to death was not the first time he used a weapon to torture her. IPV is insidious; it is subtle, gradual, and mostly invisible. The death of the victim is the most visible and culmination of her long-term ordeal.

In Sierra Leone, like in most West African countries, women carry the weight of societal expectations and the complex web of cultural norms, beliefs, and attitudes that perpetuate the cycle of IPV in society, trapping women in a silence that can be deadly.

The tragic deaths of Sia and Mariama highlight the urgent need for societal change in West Africa. To protect women and break the cycle of IPV, we must:

- Challenge cultural norms that excuse male IPV and blame female victims

- Implement and enforce more robust prosecution for IPV perpetrators

- Provide education and resources to empower women and men to recognize and combat IPV.

- Create support systems for survivors that address both immediate safety and long-term healing.

Until and unless we confront the issue of IPV head-on, the dream of a West Africa where every individual, regardless of gender, can live free from the threat of intimate partner violence will continue to be an unattainable dream. Women will continue to suffer and die in silence for generations to come. And regardless of where they end up in the world, West African women will not be safe from IPV.

Sources:

Columbus man waited until kids went to school, then killed wife with hammer and knife.